It all began when I was examining a dress and jacket suit recently accessioned to Walsall Museum’s Community Costume Collection. It was a green crepe ‘sunday best’ style outfit, with a cheery pink rose print. It is from late 1950s or early 1960s (though I could do with doing a bit more research to confirm this). In my more fanciful moments, I can picture Edith or Flora Hodson wearing it whilst bustling off to church or to some family occasion.

The green and pink floral ‘Sunday Best’ outfit found in a wardrobe at 54 New Road.

Sheila Shreeve found the outfit in a wardrobe at 54 New Road (the property was both the family home and business premises) and there had been some discussion regarding the relationship between the ensemble and the Hodson Shop Collection. The outfit has some very clear signs of wear – soiling around the neckline, evidence of altered hems and repairs and there is even a brooch pinned to the right hand bust. The Hodson Shop Collection is defined as unworn shop stock, with ‘unworn’ being the operative word in this case. Based on the evidence of wear, the outfit was ultimately accessioned into the Community Costume Collection with a note making the relationship to the Hodson Shop clear.

My own study of the garment involved examining the garment inside and out. It was during this process that I noticed the marking under the arms, the repairs in subtly different thread and the clear line of an adjusted hem. I also came across a paper label stitched into the left hand seam of the dress. I can’t find the photo of the label so I will try my best to take one on my next visit to the museum (you can see similar here). From my research notes:

A rectangular paper label is stitched into the left side seam. It is reinforced with a textile mesh on the reverse side. Measures 30mm W x 40mm H. Text is printed in black serif: “MORRISH, LONDON, W1 Ref. C. Style (stamped, red) 194 Prod. (stamped, red) 20035 Mach. (handwritten, pencil) 15 Fin. (stamped, red) 46 Presser Size (stamped, red) 44”

This is where I went wrong. Based on my own experience of clothing labels, I assumed that Morrish were the manufacturers of the outfit. After all, the labels in modern clothing always give the name of the manufacturer, right? This is where the Prownian approach (description, deduction, speculation) to analysing garments proved to be most valuable. It was time to test my hypothesis!

And it turns out that it was very, very wrong. I spent a fascinating afternoon trying to find out who Morrish were. It began, as do many modern adventures in dress history, with a hunt on eBay. I came across several vintage items listed as “Morrish & Co.”, including one rather pretty organza party frock that I came dangerously close to buying (in the name of research, of course). Things got interesting on Etsy where I noticed that listings were far more cautious, referring to ‘order labels’ bearing the name Morrish & Co., as opposed to the stating the company as the manufacturers of the garments. Lots of the garments I came across were listed as appearing to be handmade and there was no real continuity in their style (a sweet party frock one minute, a leopard print-lined leather coat the next). The next phase of my online odyssey took me to an entry on a Vintage Fashion Guild forum. A user called ‘Leonardo da Vintage’ was enquiring about a 50s wiggle dress baring a very similar label. She asked the following questions:

It has a paper hand written label sewn into a seam – what does that indicate? I’ve looked up Morrish & Co, London W1, and the only possibly relevant company made stationary, bags and then shop fittings – so perhaps they made the label, rather than the dress?

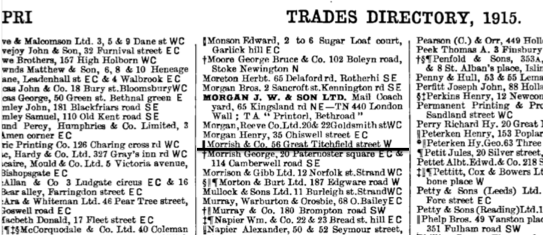

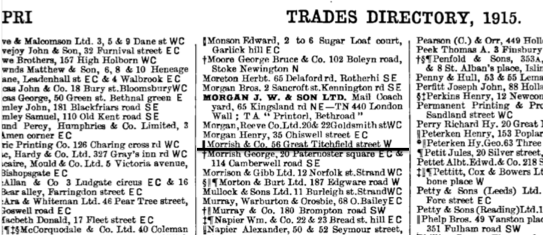

Maybe Morrish & Co. weren’t clothing manufacturers after all? Armed with the company name and postcode I decided to search through some trade directories. I hit gold in the Post Office London Directory, 1915 (you can access them via University of Leicester’s wonderful Special Collections Online ‘Historical Directories of England and Wales’) . Listed under ‘PRI’ (which is possibly short for ‘Printers’?) on page 471 I found the following entry :

The listing for Morrish & Co in the 1915 Post Office London Directory. Image via University of Leicester Special Collections Online

I then Googled ‘Morrish & Co 56 Great Titchfield Street’ and the first result was for a company called Morplan. Morplan are suppliers to the fashion industry – they provide labels, ticketing, bags and hangers amongst numerous other bits and pieces essential to clothing retail and manufacture. The ‘About’ page of the website informed me that the ‘Mor’ part of the name was taken from Mr Morrish of Camberwell, SE London who founded the company in 1845. They operated using the names ‘Morrish and Chalfont’, ‘ Morrish & Co.’, ‘Morrish’ and finally ‘Morplan’. They have been operating from Great Titchfield Street, W1 since approx. 1894.

So there’s one mystery pretty much solved: Morrish & Co. made the labels NOT the dresses. I’m not sure how much of this is common knowledge within dress history and vintage circles but it is clearly a red herring that catches many vintage sellers and students like me out. As one mysterious case closes, another one has opened: who made the green ‘Sunday Best’ outfit? I can see this turning into a mammoth trawl through the Hodson Shop Archive. I’ll let you know when I find anything out!

I’m also now beyond intrigued in the history of Morrish & Co. and their links with the fashion industry. Please let me know if you are aware of any research on them. I’ve never really stopped to think about who makes the labels in my clothing, they are one of those small and largely ignored parts of everyday life and dress. There’s a nice project in that somewhere!