Tagged: vintage

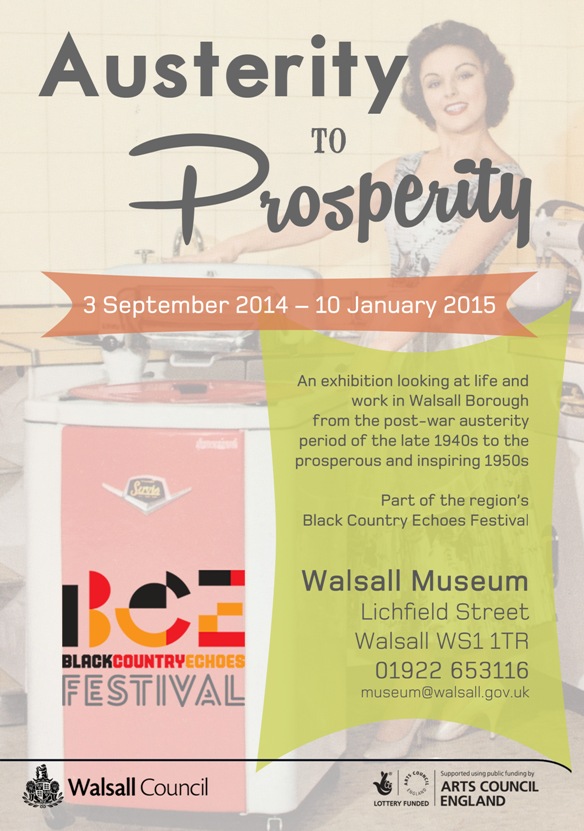

Exhibition: Austerity to Prosperity

I was honoured and excited when Walsall Museum invited me to take part in planning this exhibition. My brief was to select items from the Hodson Shop Collection that told the story of the transition from wartime austerity to the relative prosperity of the 1950s. The clothing in the collection fits perfectly within this tumultuous period and provides evidence of what Black Country women were wearing during the post-war period. There are the simple yet subduedly elegant utility (CC41) dresses that fade away as the 1950s get into full swing, with full skirts and vivid prints taking over.

My main aim was not to oversimplify the narrative of change; the myth that everyone woke up on 1st January 1950 to find that the drab wartime world had been replaced by a new consumer-driven technicolor dream world. The 1940s may have been a time of austerity but there was still colour, beauty and a booming demand for little luxuries such as lipstick and face powder. Conversely, the 1950s remained austere for many, with food rationing only coming to an end in 1954 (clothing rationing ended in 1949). I reflected this by choosing a few unusual items: a ‘Wartime emergency pack’ of face powder, a surprisingly frilly utility dress, a distinctly dreary wool jersey dress from the 1950s next to a full-skirted confection of a dress from the same time.

Utility items from the Hodson Shop Collection – creases have been kept in the dress as that is how it was discovered in the Hodson Shop.

Installing the exhibition was great fun and an excellent learning opportunity. I’m really proud of the end result, especially the bit that includes a 1950s twin-tub washing machine!

The clothing accompanies a display of items manufactured or used in the Black Country during the period 1940-1960, again reflecting the aesthetic and ideals of the shift from austerity to prosperity. The exhibition is part of the region-wide Black Country Echoes festival and runs 3 Sept-10 Jan 2015. Admission is free.

Thanks to the team at Walsall Museum for providing me with this opportunity and supporting me along the way!

From Austerity to Prosperity

3 Sept 2014-10 Jan 2015

Community History Gallery, Walsall Museum, Lichfield Street, Walsall.

The Mystery of Morrish & Co.

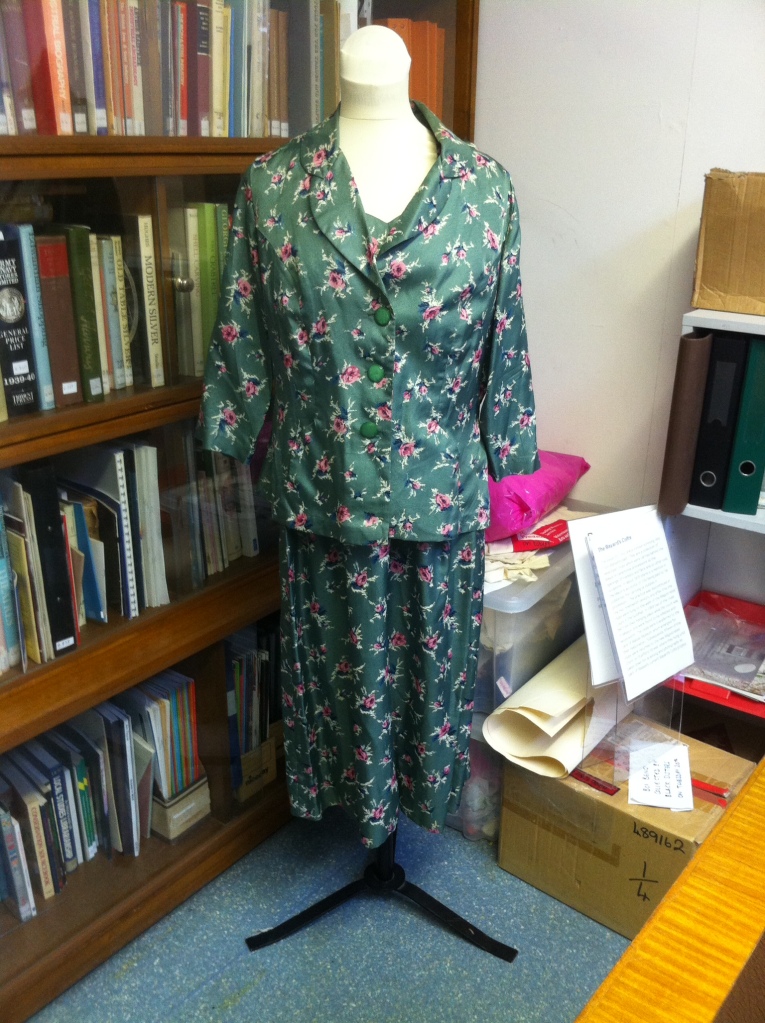

It all began when I was examining a dress and jacket suit recently accessioned to Walsall Museum’s Community Costume Collection. It was a green crepe ‘sunday best’ style outfit, with a cheery pink rose print. It is from late 1950s or early 1960s (though I could do with doing a bit more research to confirm this). In my more fanciful moments, I can picture Edith or Flora Hodson wearing it whilst bustling off to church or to some family occasion.

Sheila Shreeve found the outfit in a wardrobe at 54 New Road (the property was both the family home and business premises) and there had been some discussion regarding the relationship between the ensemble and the Hodson Shop Collection. The outfit has some very clear signs of wear – soiling around the neckline, evidence of altered hems and repairs and there is even a brooch pinned to the right hand bust. The Hodson Shop Collection is defined as unworn shop stock, with ‘unworn’ being the operative word in this case. Based on the evidence of wear, the outfit was ultimately accessioned into the Community Costume Collection with a note making the relationship to the Hodson Shop clear.

My own study of the garment involved examining the garment inside and out. It was during this process that I noticed the marking under the arms, the repairs in subtly different thread and the clear line of an adjusted hem. I also came across a paper label stitched into the left hand seam of the dress. I can’t find the photo of the label so I will try my best to take one on my next visit to the museum (you can see similar here). From my research notes:

A rectangular paper label is stitched into the left side seam. It is reinforced with a textile mesh on the reverse side. Measures 30mm W x 40mm H. Text is printed in black serif: “MORRISH, LONDON, W1 Ref. C. Style (stamped, red) 194 Prod. (stamped, red) 20035 Mach. (handwritten, pencil) 15 Fin. (stamped, red) 46 Presser Size (stamped, red) 44”

This is where I went wrong. Based on my own experience of clothing labels, I assumed that Morrish were the manufacturers of the outfit. After all, the labels in modern clothing always give the name of the manufacturer, right? This is where the Prownian approach (description, deduction, speculation) to analysing garments proved to be most valuable. It was time to test my hypothesis!

And it turns out that it was very, very wrong. I spent a fascinating afternoon trying to find out who Morrish were. It began, as do many modern adventures in dress history, with a hunt on eBay. I came across several vintage items listed as “Morrish & Co.”, including one rather pretty organza party frock that I came dangerously close to buying (in the name of research, of course). Things got interesting on Etsy where I noticed that listings were far more cautious, referring to ‘order labels’ bearing the name Morrish & Co., as opposed to the stating the company as the manufacturers of the garments. Lots of the garments I came across were listed as appearing to be handmade and there was no real continuity in their style (a sweet party frock one minute, a leopard print-lined leather coat the next). The next phase of my online odyssey took me to an entry on a Vintage Fashion Guild forum. A user called ‘Leonardo da Vintage’ was enquiring about a 50s wiggle dress baring a very similar label. She asked the following questions:

It has a paper hand written label sewn into a seam – what does that indicate? I’ve looked up Morrish & Co, London W1, and the only possibly relevant company made stationary, bags and then shop fittings – so perhaps they made the label, rather than the dress?

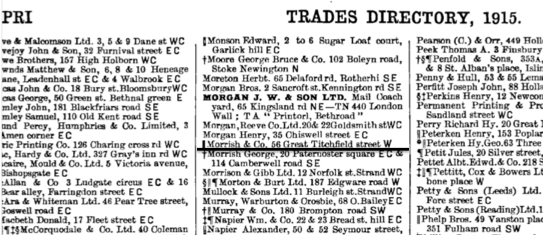

Maybe Morrish & Co. weren’t clothing manufacturers after all? Armed with the company name and postcode I decided to search through some trade directories. I hit gold in the Post Office London Directory, 1915 (you can access them via University of Leicester’s wonderful Special Collections Online ‘Historical Directories of England and Wales’) . Listed under ‘PRI’ (which is possibly short for ‘Printers’?) on page 471 I found the following entry :

The listing for Morrish & Co in the 1915 Post Office London Directory. Image via University of Leicester Special Collections Online

I then Googled ‘Morrish & Co 56 Great Titchfield Street’ and the first result was for a company called Morplan. Morplan are suppliers to the fashion industry – they provide labels, ticketing, bags and hangers amongst numerous other bits and pieces essential to clothing retail and manufacture. The ‘About’ page of the website informed me that the ‘Mor’ part of the name was taken from Mr Morrish of Camberwell, SE London who founded the company in 1845. They operated using the names ‘Morrish and Chalfont’, ‘ Morrish & Co.’, ‘Morrish’ and finally ‘Morplan’. They have been operating from Great Titchfield Street, W1 since approx. 1894.

So there’s one mystery pretty much solved: Morrish & Co. made the labels NOT the dresses. I’m not sure how much of this is common knowledge within dress history and vintage circles but it is clearly a red herring that catches many vintage sellers and students like me out. As one mysterious case closes, another one has opened: who made the green ‘Sunday Best’ outfit? I can see this turning into a mammoth trawl through the Hodson Shop Archive. I’ll let you know when I find anything out!

I’m also now beyond intrigued in the history of Morrish & Co. and their links with the fashion industry. Please let me know if you are aware of any research on them. I’ve never really stopped to think about who makes the labels in my clothing, they are one of those small and largely ignored parts of everyday life and dress. There’s a nice project in that somewhere!

Picture Post: Into the Archive…

Back in November 2013 I posted a selection of colourful and charming images from the Hodson Shop archive. Fast forward to today and I’m still working my way through the archive, though the images I’ll be sharing in this post are far less colourful and, perhaps, not quite so visually striking. Yet that’s not to say that the images are without interest or intrigue…

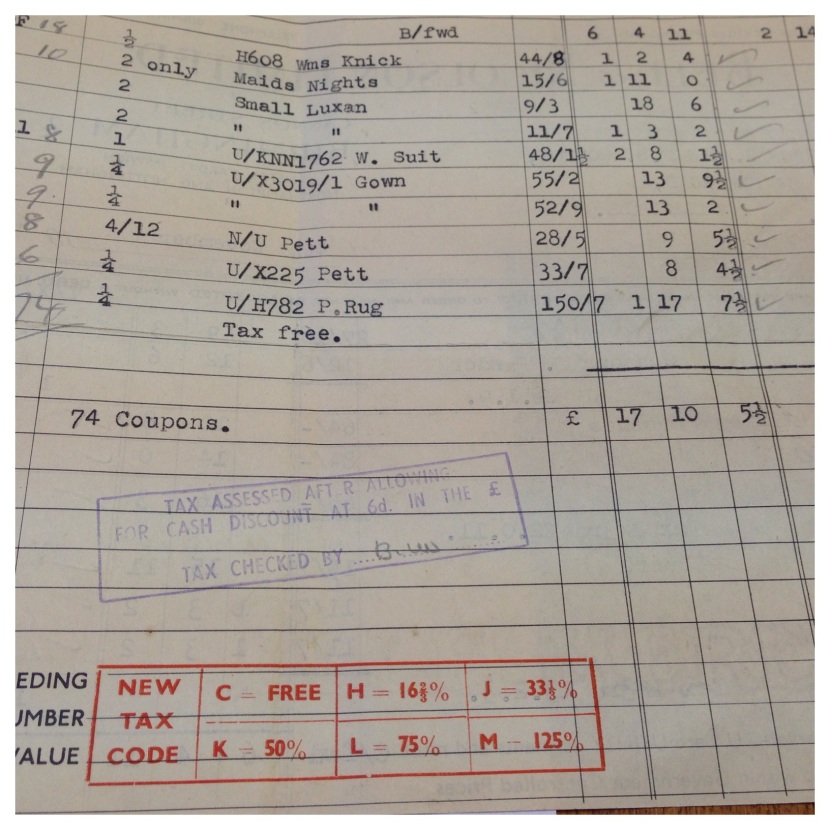

The archive contains invoices and paperwork as well as the catalogues and other ephemera. I have spent the past few weeks working my way through piles of invoices and delivery notes, searching for any links between the items listed and the objects that I have been analysing within the collection.

The aim of the process has been to build as full a biography as possible for the items. The invoices have the potential to answer a lot of questions. Where did an item come from? Who supplied them? How much did they cost? And when did they arrive? These answers can help to trace the life story of the items before their life in the Hodson Shop and Walsall Museum.

It hasn’t been easy. The invoices rarely give much in the way of descriptive detail – information regarding size or colour is a rarity and brand names tend to only crop up for specific items like corsets, hosiery and toiletries. There have been times when I have cursed the 1920s sales clerks for having such sloppy handwriting and not bothering to tell me the colour of a ‘frock’ ordered in 1923! Yet I have found some fascinating matches.

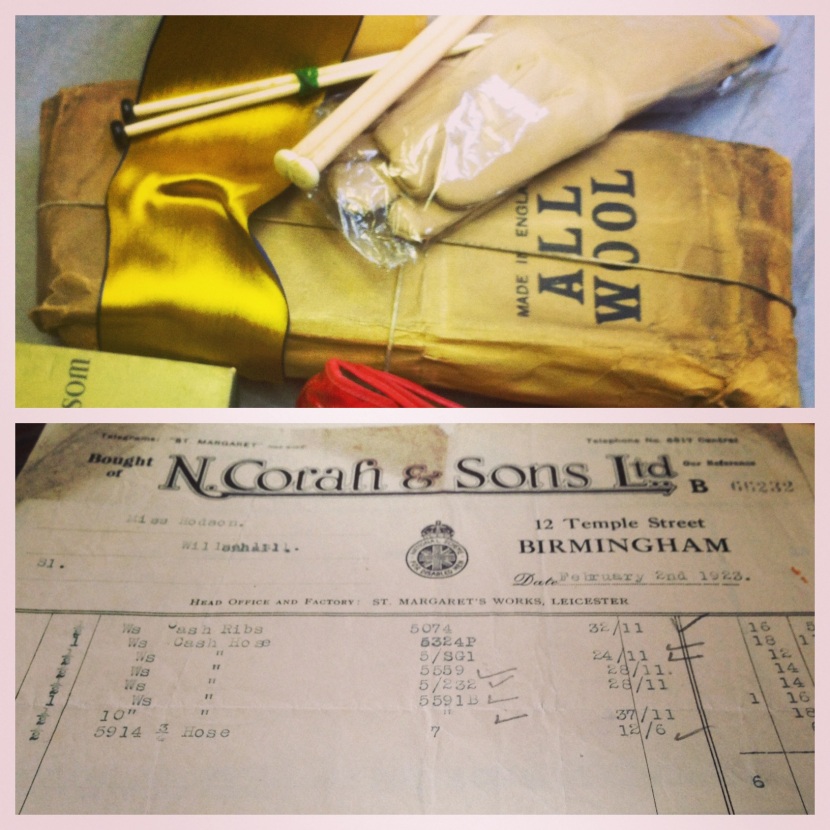

This non-descript brown paper parcel believed to contain children’s cashmere hose is likely to be the “5914 ¾ Hose” item listed on a N. Corah invoice from 2nd February 1923:

(Top) A parcel containing children’s cashmere hose (Bottom) An invoice from N. Corah & Sons Ltd., 1923 detailing the same hose.

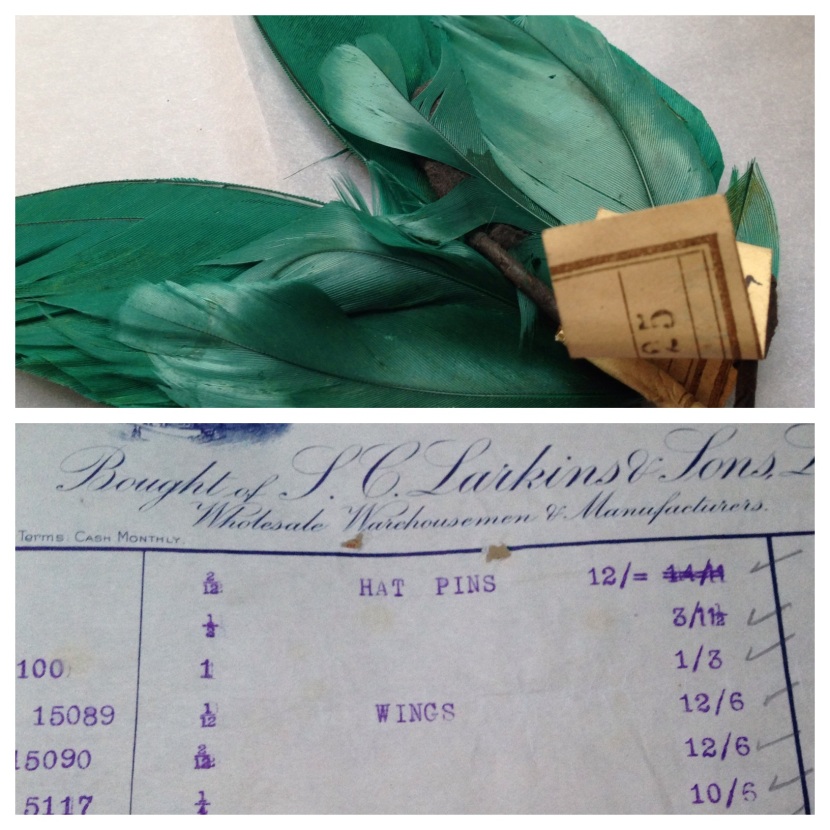

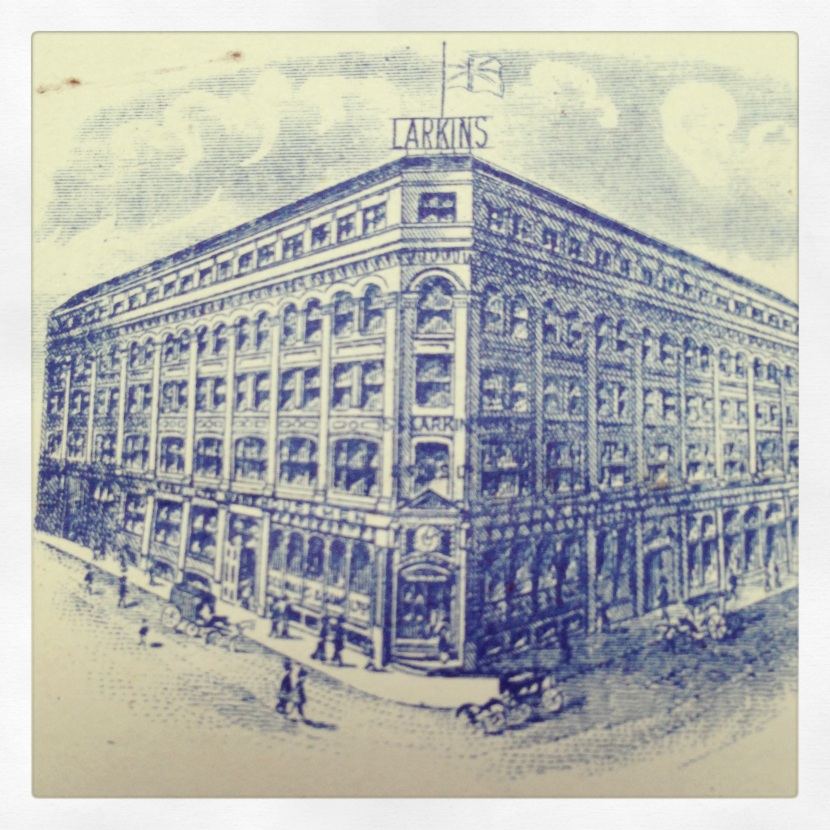

These green ‘mock wing’ feathers? They are listed as ‘Wings’ on this S.C. Larkins & Sons invoice from 18th August 1921:

(Top) Jade green mock wings (Bottom) Invoice from S.C. Larkins & Sons Ltd., 1921 listing the same product.

In both of these cases, I’ve been fortunate enough to have item codes to match up. Utility items have been slightly easier to trace, as have some items with the St. Margaret brand due to N. Corah and Sons being both manufacturers and their own wholesaler.

There have been some amusing moments – such as the terribly polite letter from a wholesaler informing Edith Hodson that she wasn’t entitled to the discount she had applied to an order. There’s also the repeated insistence of wholesalers to address Edith and Flora as ‘Sirs’ or ‘Mr Hodson’. Whilst comical to a point, I believe that this error serves to highlight quite how extraordinary Edith and Flora were, operating a business in what was very much a man’s world. They were bold and would often correct such errors. They weren’t afraid to push their luck if it meant saving money:

Letter dated 14th May 1930 from the ‘Counting House’ of N. Corah & Sons Ltd. Note the use of the greeting ‘Dear Sir’.

Something that has struck me is how much stock was coming into the shop. Invoices from some of their major suppliers are often at weekly or two weekly intervals. I need to look into it further but my initial view is that they regularly over-bought, which provides an explanation as to why the Hodson Shop Collection is so large. Another observation is that the sisters tended to only go to the trouble of returning items if they were from local suppliers, such as Walsall-based Ennals & Co. Ltd.. There are far more credit notes from this supplier than others. Maybe travelling to wholesalers further afield was too time consuming and too expensive? Or maybe their goods simply weren’t up to Edith and Flora’s standards?

The invoices themselves are visually interesting. Some feature images of the wholesalers premises, such as S.C. Larkins & Sons Ltd. of Livery Street, Birmingham:

S.C Larkins & Sons wholesalers. Premises on the junction of Livery Street and Barwick Street, Birmingham. Image from 1920 invoice.

There are still hundreds of pieces of paperwork for me to look through and I’m hugely looking forward to being able to cross reference my invoice findings with some of the links I’ve already made between certain items and trade catalogues. It has also been a thrill to see aspects of Edith and Flora Hodson’s personalities show through something as generic and functional as invoices.

Many thanks to Walsall Museum for providing me with access to the archive and for allowing me to photograph the items.

If you wish to explore the Hodson Shop Collection and Archive, please contact Walsall Museum.

Tel: 01922 653116

Email: museum@walsall.gov.uk.

Picture Post: Exploring the Hodson Shop Archives

After a busy few weeks (more on which in a future post), it has been a pleasure to finally get back to hands-on archival research. I’ve spent a few days digging through the Hodson Shop archive of trade catalogues, seeking out links to any of the items I have encountered during my object analysis. Plenty have emerged as I’ve worked my way through piles of trade brochures for Birmingham wholesalers such as Wilkinson and Riddell, S.C Larkin and Sons and Bell and Nicholson. The images below are of some of the things that have caught my eye. They aren’t always hugely relevant to my research but they are the things that have raised some intrigue, a smile or a giggle.

I’ve attempted to give as much detail as possible for each image, though I forgot to note the date and wholesaler for this Christmas apron image. I think it is late-1940s/early-1950s Bell and Nicholson, though I’ll double check when I am next at the museum and update the caption accordingly.

I’ve posted before about underwear and how the collection highlights changing attitudes and approaches to undergarments from 1920s-1960s. The 1920s Queen of Scots promotional material is a prime example of this: hygiene and comfort, alongside endorsement from a pious historical figure (c.f. Cardinal Wolsey and his stockings). This is something that I really want to do some more research into (proposed paper title: Piety, Purity and Pants). If you know of any existing work on early-20th century underwear marketing, please let me know!

The 1930s Wilkinson and Riddell catalogue covers are especially stunning – with their Japanese influences and bold artwork. There is something rather charming about their Greyhound logo, especially when placed next to a bonsai tree. The pink and yellow gladioli cover is a personal favourite.

The S.C. Larkin and Sons brochure, New Designs for 1930. Maids’ and Nurses’ Caps, revealed links to Walsall’s famous Sister Dora – the nurse and nun who revolutionised approaches to nursing during the mid-ninteenth century. She created a simple cap for nurses to wear and the brochure shows the design in a number of styles ‘suitable for bobbed hair’.

The final image is of some scribbled notes that I found inside a 1954 Bell and Nicholson catalogue, possibly by Edith or Flora Hodson. There was something eerie about coming across these notes and doodles – as if they were a direct link back to the women and what was going on inside their heads. I’ve seen their handwriting many times before but it has mainly been scrawled numbers or scrappy receipts. These notes seem more personal. And that little sketch of a head? Well, I’m filing that under ‘a bit creepy’.

Many thanks to Walsall Museum for providing me with access to the archive and for allowing me to photograph the items.

If you wish to explore the Hodson Shop Collection and Archive, please contact Walsall Museum.

Tel: 01922 653116

Email: museum@walsall.gov.uk.

Current Exhibition: Red! @ Walsall Museum

From left: printed cotton day dress, c.1951 (Hodson Shop Collection), red grosgrain short evening dress with roses, c.1958.

Sometimes it is the simplest ideas that prove to be the most effective, as evidenced by Walsall Museums latest dress exhibition: Red!

As you might have figured from the title, the exhibition is a celebration the colour red, most specifically the iconic red dress.

All of the dresses have been drawn from Walsall Museum’s massive costume collection and include several items from the Hodson Shop Collection. The dresses are organised in chronological order, starting with this stunning striped muslin day dress from the 1850s (pictured below) and working their way up to this slinky satin wrap dress from the early 1990s (I love the fact that this dress is from Etam). And somewhere in the middle is this grosgrain Wishick and Webber stunner from 1958 (pictured top right).

Hodson Shop dresses include a 1920s cotton day dress with a pointed collar and daisy print, aCC41 (utility) rayon crepe dress with a belt and button details and a 1950s floral print day dress, scattered with stripes and roses (pictured top left). Even though the Hodson dressed are far from the glitziest items on display, they certainly manage to hold their own amongst the frills and flounces.

The visual impact of the colour is undeniable, whether the dress is a glitzy beaded flapper number or a simple utility dress. It is a great starting point for planning outfits for the upcoming party season!

Red! runs until 18th January 2014 at Walsall Museum, Changing Face of Walsall Gallery on the first floor of the Walsall Central Library building. Admission is free! See What’s On Walsall for more details.

A Visit to the Hodson Shop

54 New Road, Willenhall was the site of the Hodson Shop. The building is now in the care of the Black Country Living Museum (BCLM) and goes by the name The Locksmith’s House due to Edgar Hodson’s successful lock making business that operated from the same site.

The house isn’t normally open to the public, so I jumped at the chance to go on a special visit with historian Rod Quilter. I spent a wonderful afternoon exploring 54 New Road. It felt odd to be in a place that I have read and written so much about.

Stepping into the shop, which now functions as a reception area/gift shop/mini exhibition space I was instantly struck by how small it was. My only previous experience of the space had been from a black and white photo taken in 1983 – whoever took it had obviously applied estate agent style photographic skills!

There was display case of 1920s clothing and shelves in alcoves to either side of the fireplace. In fact, the fireplace was my only real point of reference from the photograph; the display units were all new additions. The shelves held corsetry, accessories and haberdashery items – everything on display had been loaned from Walsall Museum. A door between the shop and neighbouring parlour had been filled in. The shop was accessed from the street by walking through the front door and walking a short way down a stone-floored hallway. It seemed strange for the shop to share an entrance with the rest of the house, as if the boundaries between personal and business spaces were blurred.

The parlour had been recreated with a combination of reproduction soft furnishings and original furniture. There was a booklet of photographs on a small table; it contained images of the Hodson family including a stunning photograph of a youthful Flora Hodson.

We went upstairs to a small office space; it was next door to the master bedroom – again with the blurred lines between business and private life. The bedroom was quite poignant, it was where Flora Hodson slept, alone in the house, following the death of her sister and brother.

Edgar Hodson’s lock making business is the focal point of the property. We were lucky to get a tour of his factory and some facts about lock making from a volunteer called Andy who is a locksmith himself and runs demonstrations for visitors. It turns out that Edgar supplied locks all over the world, including a booming business in Latin America.

It was fascinating to walk through the house and it got me thinking about how the collection has become separated from its original environment. I am very interested in how the historical narrative of lockmaking has been prioritised over one of shop keeping and clothing. On a more practical level, I am struggling to imagine how the collection once fitted into such a compact space!

As mentioned above, the house isn’t generally open to the public – school and group visits can be arranged by contacting the BCLM. However, the house has an annual free open day complete with tours and lock making demonstrations. The next one is Saturday 14th September, 10am-4pm. I’d highly recommend it.

Massive thanks to Jo Moody and Andy at BCLM, Catherine Lister at Walsall Museum and Rod Quilter for a wonderful afternoon!

Current Exhibition: Summer on the Beach @Walsall Museum

Fun fact: The Hodson Shop Collection contains no beachwear. I need to do a bit of digging as to why this might be but I have a couple of theories:

1) Willenhall is about as land-locked as a town can be, so a swimming costume would be more of a luxury than a necessity.

2) The Hodson Shop simply wasn’t the sort of place that sold swim wear – maybe bathing suits were purchased from more specialist retailers?

Whilst Edith and Flora Hodson might not have been purveyors of bikinis and bathing costumes, the people of Walsall borough definitely had a desire to splash around at the seaside!

Walsall Museum’s Summer on the Beach exhibition gives a vibrant overview of 20th century beachwear, drawing from the Museum’s extensive Community History Costume Collection.

Can you picture yourself parading along the beach in a psychedelic seventies bikini or sunning yourself in a floral fifties bathing suit with puffed skirt? How about dodging waves in a heavy stockinette Edwardian bathing dress? And for the men they have just the thing for taking a dip, a thick woollen swimming suit.

Summer on the Beach is on show from Thursday 13 June until Wednesday 11 September 2013. It can be seen within Walsall Museum’s Changing Face of Walsall gallery on the first floor of the Central Library building. Entry to the Museum is free of charge, for further information please contact 01922 653116 or email museum@walsall.gov.uk.

Note: The pictures below aren’t from the actual exhibition – they were taken at an event earlier in the year. Both of these swimming costumes feature in the exhibition and give a good idea of the flamboyant and colourful nature of the swimwear. I’m pretty smitten with the butterfly print number!

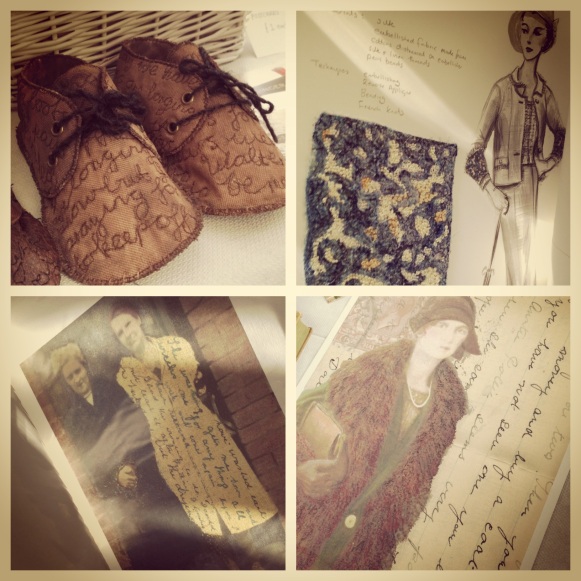

Appreciating the Pretty Things

It has been a while since my last post. I’ve been busy over the past few weeks – finishing the object analysis stage of my research, preparing for interviews with museum staff and delivering two presentations about the Hodson Shop Project.

During this time, I’ve been lucky to attend two CHORD workshops and a study day at the University of Chester about the Textile Stories project, organised by Professor Deborah Wynne. It is always a pleasure to go along to such events and meet people who are passionate about clothing and history. It is especially exciting to have a chance to talk about my research with these people!

I’m still very much in the thick of it research-wise, so this post is more a collection of some of the gorgeous images that I have captured in the course of my studies over the last month or so.

It is quite refreshing to step back from detailed analysis and to simply appreciate something because it is pretty. Some objects and garments make people smile, a factor which is arguably undervalued in studies of material culture. And sometimes that smile is enough. There are no long-winded descriptions or complex biographies for any of the items picture below. Enjoy.

Underwear and the Hodson Shop Collection

Let’s talk about underwear.

The Hodson Shop contains a lot of underwear and analysing it has been quite an eye opening experience! Let’s just say that there’s nothing like a pair of pale brown 1920s woollen knickers to make you eternally grateful for a humble pair of M&S cotton briefs.

The drab, frumpy and substantial (in both cut and fabric) nature of some of the underwear that I have been examining has highlighted one of the key dangers when using the collection to make generalisations about fashions and dress from particular eras. It is quite easy to look at items from, say, the 1920s and use them to create a vision of what people wore during that period. Yet caution is required.

Garments in the collection are there for a simple reason: no one ever purchased them. This could be a case of the Hodson sisters buying in far too many items and refusing to have stock clearance sales or it could be that they were simply stocking things that no one wanted.

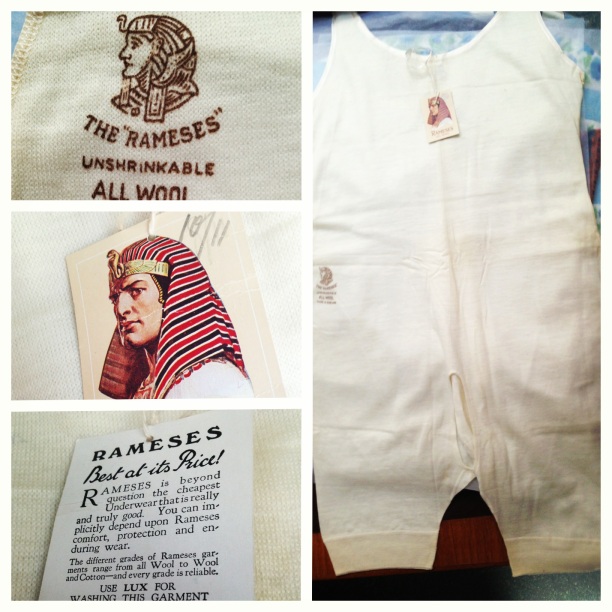

Take this 1930s woollen combination (below). It is made by the fabulously named ‘Rameses’. The first thing I noticed was the sheer weight and thickness of the fabric, I then noticed the open crotch and I have to admit that that there were giggles. To 21st century eyes, the garment has an almost comic quality. It is a world away from the ‘sexy’ briefs and bras that stuff underwear drawers across the country. In fact, it is a world away from ‘sexy’ fullstop!

Forget Agent Provocateur or Coco de Mer, this is underwear that was intended to perform a function. The open crotch, for example, was there to enable the wearer use the toilet without having to get undressed. That’s not to say that the wearers of such garments didn’t get frisky when the urge so took them…

The Hodson Shop would have needed to cater for their older customer. So during the 1920s and 1930s when many of Willenhall’s young ladies would have been donning shorter skirts, some Hodson Shop customers were possibly still sporting Edwardian-era ankle length skirts. In that context, a knee length woollen combination with a split crotch begins to make something resembling sense.

These are items that were out of fashion even at the point of potential sale. They make regular appearances throughout the collection as the customers who would have worn them were dying out or adapting to new styles of underwear.

There is a general trend emerging through the collection of undergarments becoming smaller (and often prettier) as time progresses. A Utility bra is made in a delicate shade of rose, with ribbon straps; a 1950s slip has chiffon flounces printed with trailing flowers (see above). I am also beginning to notice a shift in the promotional text used on swing tickets and labels. Earlier garments are accompanied with copy that emphasises their value, durability and quality. Vests are ‘Unshrinkable’ and ‘Protective’ (see image of the ‘Rameses’ combination above). There is also an emphasis on the ‘purity’ of the fabrics used. I am yet to observe such text accompanying underwear from 1940s-50s. This possibly gives a few hints about how social attitudes towards women, dress and sexuality were changing.

The Mysterious Case of the Blue Slippers

Studying unworn historical clothing is an unusual experience. I’m constantly looking for minute and subtle points of interest – be it a loose thread here or a tell-tale price tag there. I’m always looking for clues to a story, albeit one that doesn’t involve contact with a body.

What I never really anticipated was to find anything close to resembling ‘signs of wear’. Being ‘unworn’ is such a crucial and defining part of the Hodson Shop Collection that I’d put such matters to the back of my mind, that was until I encountered the mysterious case of the blue slippers…

They are a pair of mid-blue synthetic leather (what I prefer to call ‘pleather’ in non-academic settings!) house slippers, with a chunky curved heel, an ‘opera slipper’ style curved raised vamp and a bow at the front. They look quite smart and passable for daywear until you see the fluffy white fleece lining. My guess is that they are from the 1930s, though they may be earlier. Their condition in generally very good but I’m starting to suspect that their few scratches and creases hold a secret.

Time for a fun game of spot the difference: look at the pair of slippers below, can you spot any differences between the slipper on the left and the one on the right?

Don’t worry if not. I didn’t at see much first, but after an hour of examining them some subtle and potentially very interesting differences began to become clear.

The first thing that I noticed was that the bow on the right shoe (pictured above left) was far more curled and misshapen. This then lead me to noting scratches and worn stitching on the right shoe but not on the left. Close examination of the soles also presents a difference – there are lines of vertical scuffing on the right slipper but not the left, and some notable scratches close to the sole edge. Then I spotted something that could hold the key to these small differences. In the image below left you’ll notice that the right slipper (on left in picture) is far more collapsed than that of the left – almost as if it has been ‘trodden’ down. ‘Trodden’ being the operative word here.

This is where I start to get far too excited…

…could one of these shoes have been worn?

My initial (and the cause of my excitement) theory is that the right shoe was the ‘trying on’ slipper. We are all familiar with walking into a shoe shop and trying on shoes from display. I’ve certainly experienced that oh-so-disappointing feeling of buying some bargain shoes only to get home and discover that one is discoloured from bright shop lights and slightly crumpled from repeated trying on in-store. Maybe the Hodson sisters allowed customers to try on a single shoe in the store, retaining the matching shoe in storage?

Before I get carried away, I have to remember that there are numerous explanations behind these differences and the likelihood of me ever reaching a definitive one is very slim. Possible explanations include:

- Storage: Conditions in the Hodson Shop were far from ideal. Boxes were piled up and stock was scattered about. All it would have taken is for one shoe to get crushed by a box above or for the pair to have become separated amongst the chaos.

- Age: These shoes are approximately 80 years old. Worn or unworn, they are bound to show signs of deterioration in condition.

- Manufacture: The differences could merely be the result of inconsistencies in manufacture.

- Display: The shoes could have been on display at the shop or even during their museum life.

There’s also the argument that my brain has become so receptive to ‘signs of a story’ that I could be seeing something where there is really nothing to see.

If it were to transpire that these slippers had been tried on, I am still left with the question ‘how does this change the object?’. This question goes beyond the physical realm and raises issues around interpretation and biography. Also, it opens up a discussion around defining ‘wear’. At what point does something become ‘worn’? Can a shoe that has been slipped on and off a human foot be considered ‘unworn’?