Tagged: 1920s

Audio: Purity, Piety and Pants – The Religious Body in Early-20th Century Underwear Marketing

I’m thrilled to be able to share this audio file of my recent conference paper with you.

This recording is by no means the finished article but I have noticed that the subject really captures people’s attention so it felt right to share it. There is a lot more work and research to be done on the subject – especially concerning anxieties around the adulteration and cleanliness of fabrics.

In the meantime, I hope that you enjoy listening and I welcome any thoughts or ideas in the comments below.

Thanks to the wonderful Katrina Maitland-Brown for making this recording and to everyone at CHORD for the opportunity to speak at their workshop. As always, massive thanks to the team at Walsall Museum for their ongoing support.

References:

C. Willett and Phillis Cunnington, The History of Underclothes, (London: Faber, 1981).

Keith Jopp, Corah of Leicester 1815-1965, (privately printed, 1965). (read the PDF here)

C.W Webb, An Historical Record of N.Corah & Sons Ltd., (privately printed, 1947). (read the PDF here)

Elizabeth Ewing, Everyday Dress 1650-1900, (London: B.T Batsford Ltd., 1989).

Also see the ‘About’ section of the Wolsey website for their take on the brand’s history.

Purity, Piety and Pants

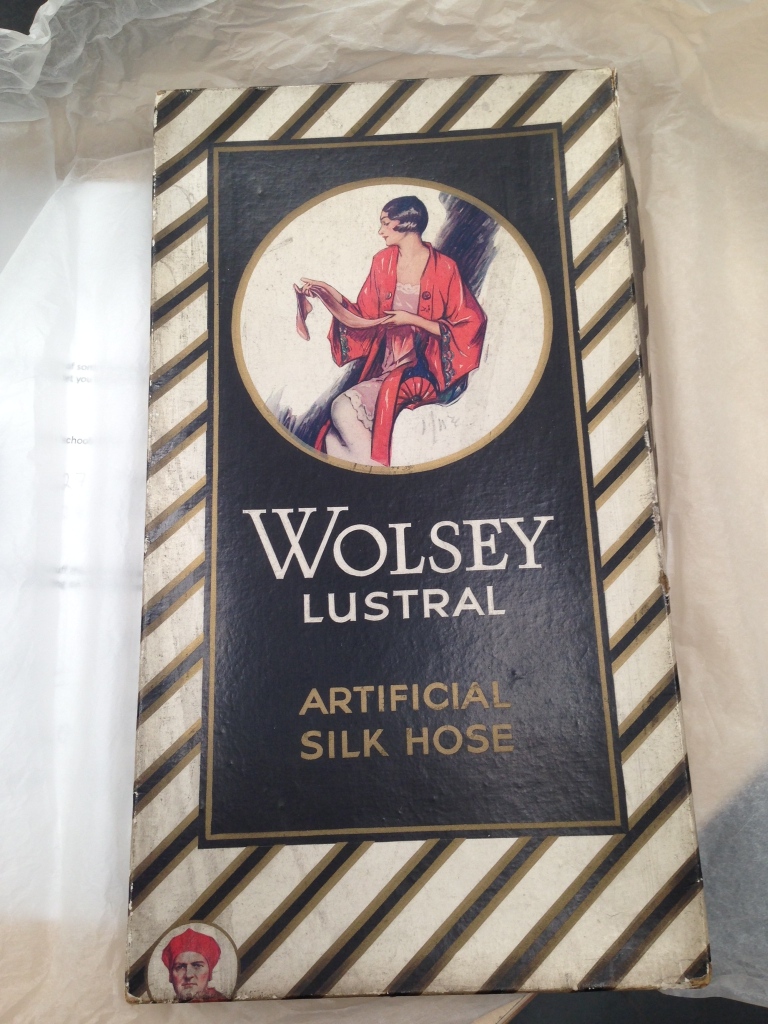

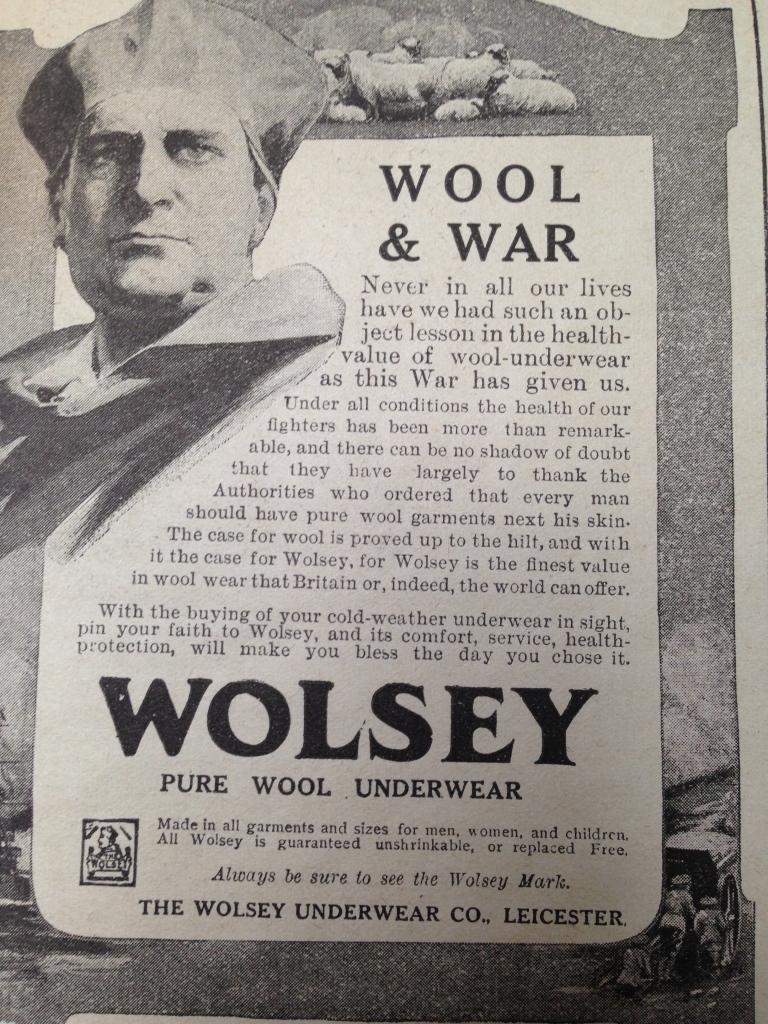

Several months ago, I (half-jokingly) mentioned my plans to write a paper about religion and underwear marketing. It was one of those situations where I knew there was something in the idea but it took me a while to get to the bottom of exactly what it was. After mulling the idea over and getting over the fits of giggles that struck me down every time I saw Cardinal Wolsey’s face on a pair of knickers, I decided to seriously pursue the idea.

I submitted an abstract for the Centre for the History of Retailing and Distribution workshop on retailing and the human body and was delighted when I was told that it had been successful. Since then I’ve become immersed in the world of early-twentieth century underwear, Thomas Wolsey and St. Margaret.

The CHORD workshop ‘Retailing, Commerce and the Human Body: Historical Approaches’ takes place on 14th May 2014 at University of Wolverhampton. Visit the CHORD webpage for more information.

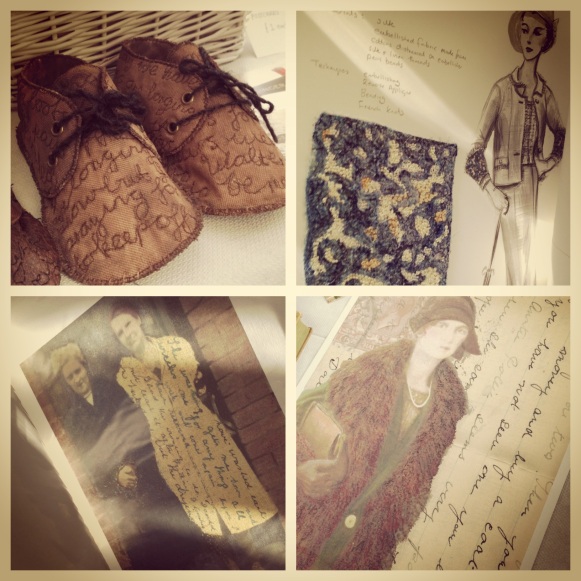

I’ll publish a summary of my paper on here after the event, but for now I wanted to share some of the images I have gathered whilst researching the paper:

As always, massive thanks to the team at Walsall Museum for allowing me to study and photograph these items!

Picture Post: Into the Archive…

Back in November 2013 I posted a selection of colourful and charming images from the Hodson Shop archive. Fast forward to today and I’m still working my way through the archive, though the images I’ll be sharing in this post are far less colourful and, perhaps, not quite so visually striking. Yet that’s not to say that the images are without interest or intrigue…

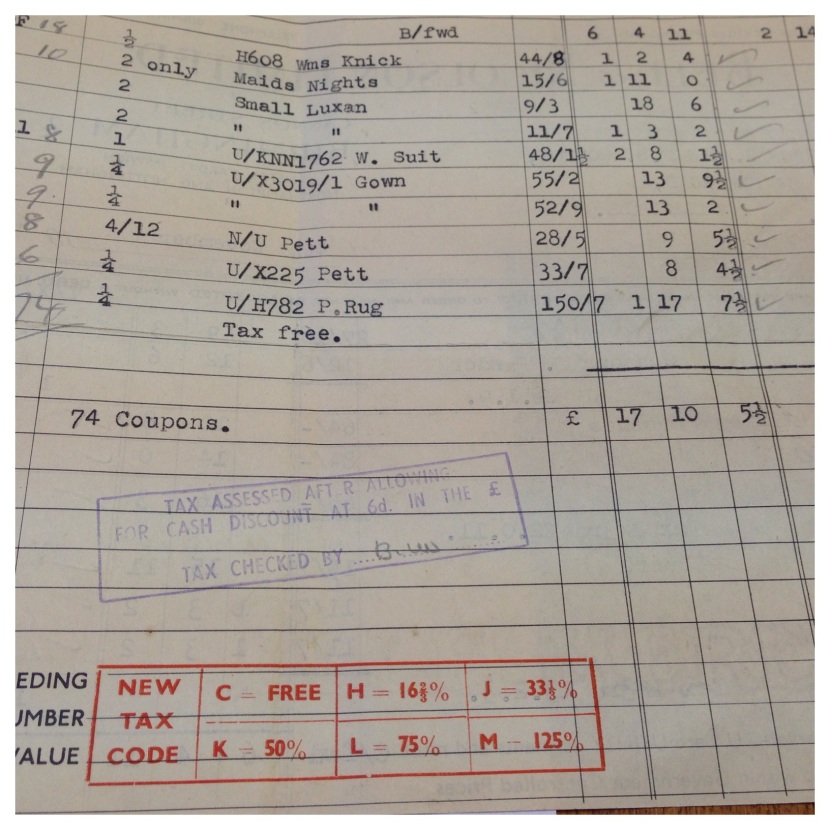

The archive contains invoices and paperwork as well as the catalogues and other ephemera. I have spent the past few weeks working my way through piles of invoices and delivery notes, searching for any links between the items listed and the objects that I have been analysing within the collection.

The aim of the process has been to build as full a biography as possible for the items. The invoices have the potential to answer a lot of questions. Where did an item come from? Who supplied them? How much did they cost? And when did they arrive? These answers can help to trace the life story of the items before their life in the Hodson Shop and Walsall Museum.

It hasn’t been easy. The invoices rarely give much in the way of descriptive detail – information regarding size or colour is a rarity and brand names tend to only crop up for specific items like corsets, hosiery and toiletries. There have been times when I have cursed the 1920s sales clerks for having such sloppy handwriting and not bothering to tell me the colour of a ‘frock’ ordered in 1923! Yet I have found some fascinating matches.

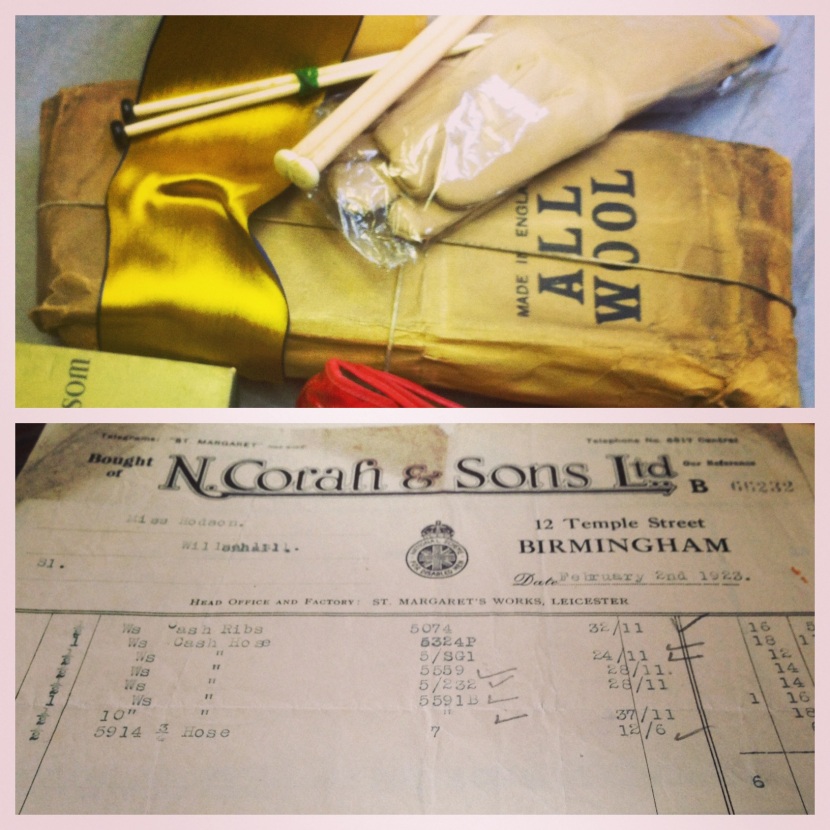

This non-descript brown paper parcel believed to contain children’s cashmere hose is likely to be the “5914 ¾ Hose” item listed on a N. Corah invoice from 2nd February 1923:

(Top) A parcel containing children’s cashmere hose (Bottom) An invoice from N. Corah & Sons Ltd., 1923 detailing the same hose.

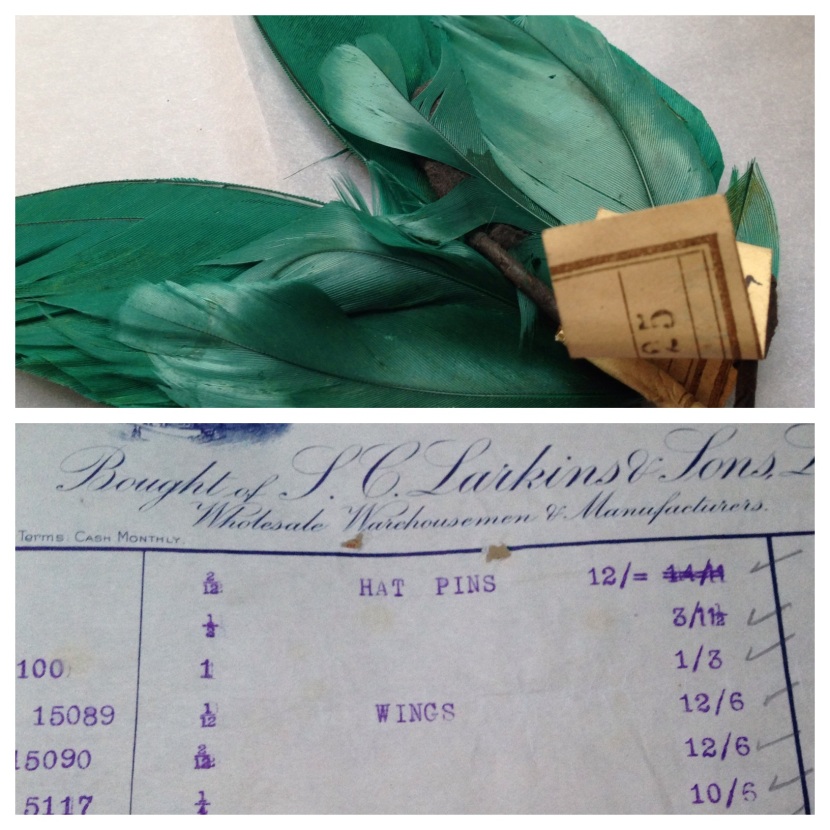

These green ‘mock wing’ feathers? They are listed as ‘Wings’ on this S.C. Larkins & Sons invoice from 18th August 1921:

(Top) Jade green mock wings (Bottom) Invoice from S.C. Larkins & Sons Ltd., 1921 listing the same product.

In both of these cases, I’ve been fortunate enough to have item codes to match up. Utility items have been slightly easier to trace, as have some items with the St. Margaret brand due to N. Corah and Sons being both manufacturers and their own wholesaler.

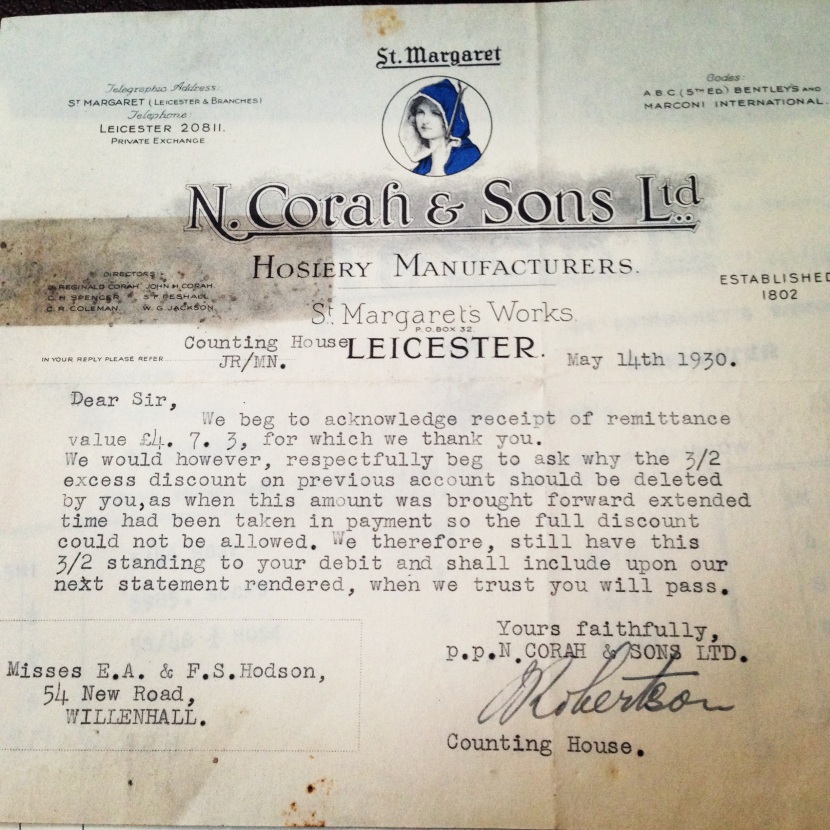

There have been some amusing moments – such as the terribly polite letter from a wholesaler informing Edith Hodson that she wasn’t entitled to the discount she had applied to an order. There’s also the repeated insistence of wholesalers to address Edith and Flora as ‘Sirs’ or ‘Mr Hodson’. Whilst comical to a point, I believe that this error serves to highlight quite how extraordinary Edith and Flora were, operating a business in what was very much a man’s world. They were bold and would often correct such errors. They weren’t afraid to push their luck if it meant saving money:

Letter dated 14th May 1930 from the ‘Counting House’ of N. Corah & Sons Ltd. Note the use of the greeting ‘Dear Sir’.

Something that has struck me is how much stock was coming into the shop. Invoices from some of their major suppliers are often at weekly or two weekly intervals. I need to look into it further but my initial view is that they regularly over-bought, which provides an explanation as to why the Hodson Shop Collection is so large. Another observation is that the sisters tended to only go to the trouble of returning items if they were from local suppliers, such as Walsall-based Ennals & Co. Ltd.. There are far more credit notes from this supplier than others. Maybe travelling to wholesalers further afield was too time consuming and too expensive? Or maybe their goods simply weren’t up to Edith and Flora’s standards?

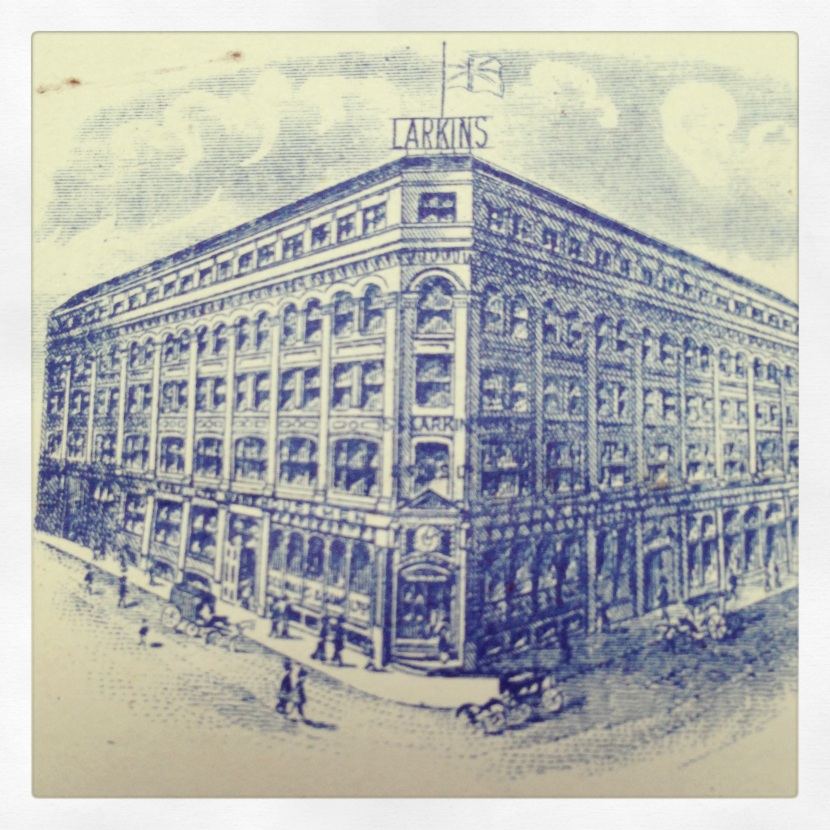

The invoices themselves are visually interesting. Some feature images of the wholesalers premises, such as S.C. Larkins & Sons Ltd. of Livery Street, Birmingham:

S.C Larkins & Sons wholesalers. Premises on the junction of Livery Street and Barwick Street, Birmingham. Image from 1920 invoice.

There are still hundreds of pieces of paperwork for me to look through and I’m hugely looking forward to being able to cross reference my invoice findings with some of the links I’ve already made between certain items and trade catalogues. It has also been a thrill to see aspects of Edith and Flora Hodson’s personalities show through something as generic and functional as invoices.

Many thanks to Walsall Museum for providing me with access to the archive and for allowing me to photograph the items.

If you wish to explore the Hodson Shop Collection and Archive, please contact Walsall Museum.

Tel: 01922 653116

Email: museum@walsall.gov.uk.

Picture Post: Exploring the Hodson Shop Archives

After a busy few weeks (more on which in a future post), it has been a pleasure to finally get back to hands-on archival research. I’ve spent a few days digging through the Hodson Shop archive of trade catalogues, seeking out links to any of the items I have encountered during my object analysis. Plenty have emerged as I’ve worked my way through piles of trade brochures for Birmingham wholesalers such as Wilkinson and Riddell, S.C Larkin and Sons and Bell and Nicholson. The images below are of some of the things that have caught my eye. They aren’t always hugely relevant to my research but they are the things that have raised some intrigue, a smile or a giggle.

I’ve attempted to give as much detail as possible for each image, though I forgot to note the date and wholesaler for this Christmas apron image. I think it is late-1940s/early-1950s Bell and Nicholson, though I’ll double check when I am next at the museum and update the caption accordingly.

I’ve posted before about underwear and how the collection highlights changing attitudes and approaches to undergarments from 1920s-1960s. The 1920s Queen of Scots promotional material is a prime example of this: hygiene and comfort, alongside endorsement from a pious historical figure (c.f. Cardinal Wolsey and his stockings). This is something that I really want to do some more research into (proposed paper title: Piety, Purity and Pants). If you know of any existing work on early-20th century underwear marketing, please let me know!

The 1930s Wilkinson and Riddell catalogue covers are especially stunning – with their Japanese influences and bold artwork. There is something rather charming about their Greyhound logo, especially when placed next to a bonsai tree. The pink and yellow gladioli cover is a personal favourite.

The S.C. Larkin and Sons brochure, New Designs for 1930. Maids’ and Nurses’ Caps, revealed links to Walsall’s famous Sister Dora – the nurse and nun who revolutionised approaches to nursing during the mid-ninteenth century. She created a simple cap for nurses to wear and the brochure shows the design in a number of styles ‘suitable for bobbed hair’.

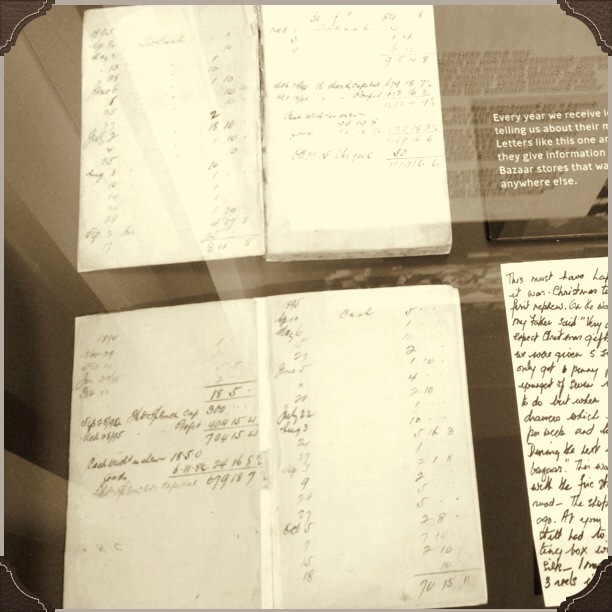

The final image is of some scribbled notes that I found inside a 1954 Bell and Nicholson catalogue, possibly by Edith or Flora Hodson. There was something eerie about coming across these notes and doodles – as if they were a direct link back to the women and what was going on inside their heads. I’ve seen their handwriting many times before but it has mainly been scrawled numbers or scrappy receipts. These notes seem more personal. And that little sketch of a head? Well, I’m filing that under ‘a bit creepy’.

Many thanks to Walsall Museum for providing me with access to the archive and for allowing me to photograph the items.

If you wish to explore the Hodson Shop Collection and Archive, please contact Walsall Museum.

Tel: 01922 653116

Email: museum@walsall.gov.uk.

Current Exhibition: Red! @ Walsall Museum

From left: printed cotton day dress, c.1951 (Hodson Shop Collection), red grosgrain short evening dress with roses, c.1958.

Sometimes it is the simplest ideas that prove to be the most effective, as evidenced by Walsall Museums latest dress exhibition: Red!

As you might have figured from the title, the exhibition is a celebration the colour red, most specifically the iconic red dress.

All of the dresses have been drawn from Walsall Museum’s massive costume collection and include several items from the Hodson Shop Collection. The dresses are organised in chronological order, starting with this stunning striped muslin day dress from the 1850s (pictured below) and working their way up to this slinky satin wrap dress from the early 1990s (I love the fact that this dress is from Etam). And somewhere in the middle is this grosgrain Wishick and Webber stunner from 1958 (pictured top right).

Hodson Shop dresses include a 1920s cotton day dress with a pointed collar and daisy print, aCC41 (utility) rayon crepe dress with a belt and button details and a 1950s floral print day dress, scattered with stripes and roses (pictured top left). Even though the Hodson dressed are far from the glitziest items on display, they certainly manage to hold their own amongst the frills and flounces.

The visual impact of the colour is undeniable, whether the dress is a glitzy beaded flapper number or a simple utility dress. It is a great starting point for planning outfits for the upcoming party season!

Red! runs until 18th January 2014 at Walsall Museum, Changing Face of Walsall Gallery on the first floor of the Walsall Central Library building. Admission is free! See What’s On Walsall for more details.

The M&S Archive and CHORD 2013

What does the Hodson Shop have in common with Marks and Spencer? “Not a vast amount beyond selling clothes” would have been my initial answer but that has changed somewhat since spending a day at the M&S Archive.

I was there for the CHORD 2013 conference on historical perspectives around retailing and the senses. The papers were fascinating, as ever. I particularly enjoyed Anneleen Arnout’s paper on the sensory aspects of the Galeries Saint-Hubert in 19th century Brussels and Ai Hisano’s history of cellophane in US food packaging. Ben Highmore’s take on Habitat’s “sensual orchestration” really got me thinking about shops as both retail and educational spaces – where people learn about design through their senses. There are clear parallels with museums within this, though this post isn’t the place for me to ramble on about those!

Instead, I want to tell you all about the M&S Archive and explain how it links with the Hodson Shop Project.

The archive contains approximately 70,000 items and is located within the Michael Marks building, University of Leeds. There’s an exhibition space on the ground floor, which is well worth a visit. The display cases contain items that tell the story of M&S over the decades – from the Penny Bazaars of the 1890s to the present day of Per Una and Percy Pigs. Researchers can also arrange access to the collections and there are excellent facilities for study.

There were some fabulous items on display. I couldn’t get over the floral print on this pair of early “Shapewear” pants (above)! The knitted swimwear from the 1920s also raised a few smiles. Yet it wasn’t all about clothing. In fact, garments only account for 1,700 items within the archive, with the rest being mainly documents relating to management, finance and product design and innovation.

Our guide, Katherine Carter explained to us that it is often a mad scramble to ensure that evidence and artefacts are collected and archived due to the fast pace of 21st century retail. Their collecting policy for clothing is to keep samples of ‘high volume sellers’ (this could be something as simple as a plain white t-shirt), garments seen on celebrities and public figures (e.g. Samantha Cameron’s polka dot dress) and garments incorporating significant innovations in textile technology.

We got to look at the ‘strong room’ where the collection is stored. I was impressed by the high-tech racking system they have in place and the pristine orderliness of the clothing collection. The garments may not have huge monetary worth and be distinctly ‘everyday’ but M&S clearly value their history.

During our tour of the exhibition space, Katherine explained how the company had evolved from a market stall in Leeds to the globally recognisable super-brand of today. It is strange to think that one of the earliest big sellers was sheet music that sold for one penny. The inflation of the 1920s made the ground breaking ‘everything’s a penny’ sales strategy impossible to maintain, leading the company to diversify and experiment with new products and branding. They introduced their first bra in 1926 and started to sell a range of simple, loose fitting garments (the loose fit was necessary due to the infancy of mass production techniques).

I was intrigued to hear that M&S technologists had worked with the government during WWII to develop what would become the CC41 (utility) scheme. It was striking to see a simple, yet elegant, utility dress next to the full and flouncy fifties floral frock. Katherine used the phrase ‘wonder fabrics’ when talking about the scientific breakthroughs of the fifties that kick started the period love affair with man-made fibres.

The 1960-1970s case was a delight. It was amusing to see how the company had attempted to keep up with the youthful freedom of the period – their first campaign with Twiggy was launched in 1968, whilst their Young St Michael range was endearingly innocent and ever-so slightly wide of the mark!

Ready meals and convenience foods were highlighted as the next major breakthrough. The not very appetisingly named ‘Boil in the Bag Ravioli’ was launched in 1971, with Indian ready meals and lasagnes following in 1972. Apparently, they were edible status symbols – with high price tags.

Fast-forwarding to 2009 and M&S celebrated the 150th anniversary of Michael Marks’ birth. The display featured limited edition archive-based garments. This anniversary marked the point when the design team began to search through the archives for creative inspiration.

There were also displays of staff uniforms from across the decades – from the early floor length black dresses worn with crisp white aprons, to the man-made fibre extravaganzas of the 1950s. A visitor assistant called Janet kindly talked me through these displays. She had worked for M&S since she was a teenager and even showed me a picture of her young self in a smart M&S uniform! She told me how her employers trained her in everything from grooming to dental hygiene. There is a clear sense of ‘family’ amongst M&S employees.

Janet also pointed me to a cabinet containing diaries belonging to Michael Marks and Tom Spencer for 1894 (the first year of the partnership). They detail Tom Spencer’s initial £300 investment in the company – humble items that capture a turning point in retail history.

So what exactly do the Hodson Shop Collection and M&S archive have in common? My first thought was that they are both collections of stock and documentation of a single business. They also cover a similar time period. In both cases, items are not spectacular, expensive or glamorous. The garments in the M&S collection are not displayed in relation to a specific wearer – making them, in a sense, ‘unworn’ (I would love to establish how many of the garments in their collection have been worn and how many have not). On a more practical level, I noticed that some of the brands featured in earlier displays were the same as found in the Hodson Shop Collection, such as Dewhurst’s and St Margaret (the latter being the inspiration behind the St Michael brand name which was dropped in 2000).

Whilst there are some parallels, I am aware that the items in the M&S archive are there due to their association with a much-loved and renowned brand and business. Michael Marks and Tom Spencer have a lofty position in retail history whilst Edith and Flora Hodson are minor players. People visit the M&S exhibition because it resonates with them on a personal level and this resonance is widespread, across the country and generations.

Massive thanks to: the team at the M&S archive (especially Katherine and Janet), Laura Ugolini and Karin Dannehl from University of Wolverhampton who organised the CHORD conference and all of the speakers at the event.

A Visit to the Hodson Shop

54 New Road, Willenhall was the site of the Hodson Shop. The building is now in the care of the Black Country Living Museum (BCLM) and goes by the name The Locksmith’s House due to Edgar Hodson’s successful lock making business that operated from the same site.

The house isn’t normally open to the public, so I jumped at the chance to go on a special visit with historian Rod Quilter. I spent a wonderful afternoon exploring 54 New Road. It felt odd to be in a place that I have read and written so much about.

Stepping into the shop, which now functions as a reception area/gift shop/mini exhibition space I was instantly struck by how small it was. My only previous experience of the space had been from a black and white photo taken in 1983 – whoever took it had obviously applied estate agent style photographic skills!

There was display case of 1920s clothing and shelves in alcoves to either side of the fireplace. In fact, the fireplace was my only real point of reference from the photograph; the display units were all new additions. The shelves held corsetry, accessories and haberdashery items – everything on display had been loaned from Walsall Museum. A door between the shop and neighbouring parlour had been filled in. The shop was accessed from the street by walking through the front door and walking a short way down a stone-floored hallway. It seemed strange for the shop to share an entrance with the rest of the house, as if the boundaries between personal and business spaces were blurred.

The parlour had been recreated with a combination of reproduction soft furnishings and original furniture. There was a booklet of photographs on a small table; it contained images of the Hodson family including a stunning photograph of a youthful Flora Hodson.

We went upstairs to a small office space; it was next door to the master bedroom – again with the blurred lines between business and private life. The bedroom was quite poignant, it was where Flora Hodson slept, alone in the house, following the death of her sister and brother.

Edgar Hodson’s lock making business is the focal point of the property. We were lucky to get a tour of his factory and some facts about lock making from a volunteer called Andy who is a locksmith himself and runs demonstrations for visitors. It turns out that Edgar supplied locks all over the world, including a booming business in Latin America.

It was fascinating to walk through the house and it got me thinking about how the collection has become separated from its original environment. I am very interested in how the historical narrative of lockmaking has been prioritised over one of shop keeping and clothing. On a more practical level, I am struggling to imagine how the collection once fitted into such a compact space!

As mentioned above, the house isn’t generally open to the public – school and group visits can be arranged by contacting the BCLM. However, the house has an annual free open day complete with tours and lock making demonstrations. The next one is Saturday 14th September, 10am-4pm. I’d highly recommend it.

Massive thanks to Jo Moody and Andy at BCLM, Catherine Lister at Walsall Museum and Rod Quilter for a wonderful afternoon!

Appreciating the Pretty Things

It has been a while since my last post. I’ve been busy over the past few weeks – finishing the object analysis stage of my research, preparing for interviews with museum staff and delivering two presentations about the Hodson Shop Project.

During this time, I’ve been lucky to attend two CHORD workshops and a study day at the University of Chester about the Textile Stories project, organised by Professor Deborah Wynne. It is always a pleasure to go along to such events and meet people who are passionate about clothing and history. It is especially exciting to have a chance to talk about my research with these people!

I’m still very much in the thick of it research-wise, so this post is more a collection of some of the gorgeous images that I have captured in the course of my studies over the last month or so.

It is quite refreshing to step back from detailed analysis and to simply appreciate something because it is pretty. Some objects and garments make people smile, a factor which is arguably undervalued in studies of material culture. And sometimes that smile is enough. There are no long-winded descriptions or complex biographies for any of the items picture below. Enjoy.

Underwear and the Hodson Shop Collection

Let’s talk about underwear.

The Hodson Shop contains a lot of underwear and analysing it has been quite an eye opening experience! Let’s just say that there’s nothing like a pair of pale brown 1920s woollen knickers to make you eternally grateful for a humble pair of M&S cotton briefs.

The drab, frumpy and substantial (in both cut and fabric) nature of some of the underwear that I have been examining has highlighted one of the key dangers when using the collection to make generalisations about fashions and dress from particular eras. It is quite easy to look at items from, say, the 1920s and use them to create a vision of what people wore during that period. Yet caution is required.

Garments in the collection are there for a simple reason: no one ever purchased them. This could be a case of the Hodson sisters buying in far too many items and refusing to have stock clearance sales or it could be that they were simply stocking things that no one wanted.

Take this 1930s woollen combination (below). It is made by the fabulously named ‘Rameses’. The first thing I noticed was the sheer weight and thickness of the fabric, I then noticed the open crotch and I have to admit that that there were giggles. To 21st century eyes, the garment has an almost comic quality. It is a world away from the ‘sexy’ briefs and bras that stuff underwear drawers across the country. In fact, it is a world away from ‘sexy’ fullstop!

Forget Agent Provocateur or Coco de Mer, this is underwear that was intended to perform a function. The open crotch, for example, was there to enable the wearer use the toilet without having to get undressed. That’s not to say that the wearers of such garments didn’t get frisky when the urge so took them…

The Hodson Shop would have needed to cater for their older customer. So during the 1920s and 1930s when many of Willenhall’s young ladies would have been donning shorter skirts, some Hodson Shop customers were possibly still sporting Edwardian-era ankle length skirts. In that context, a knee length woollen combination with a split crotch begins to make something resembling sense.

These are items that were out of fashion even at the point of potential sale. They make regular appearances throughout the collection as the customers who would have worn them were dying out or adapting to new styles of underwear.

There is a general trend emerging through the collection of undergarments becoming smaller (and often prettier) as time progresses. A Utility bra is made in a delicate shade of rose, with ribbon straps; a 1950s slip has chiffon flounces printed with trailing flowers (see above). I am also beginning to notice a shift in the promotional text used on swing tickets and labels. Earlier garments are accompanied with copy that emphasises their value, durability and quality. Vests are ‘Unshrinkable’ and ‘Protective’ (see image of the ‘Rameses’ combination above). There is also an emphasis on the ‘purity’ of the fabrics used. I am yet to observe such text accompanying underwear from 1940s-50s. This possibly gives a few hints about how social attitudes towards women, dress and sexuality were changing.

The ‘Tinkerbell’ Dress and Exhibiting the Unexhibitable

Since starting this project, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about dirt and decay. Most specifically the importance of dirt in creating a ‘biography’ for museum garments and the curatorial and conservational challenges it poses.

Here’s the deal: when the Hodson Shop Collection was first discovered, it was dirty. Years of accumulated Black Country grime had taken its toll and left garments smeared with sooty smudges. Yet the decision was made to preserve this grime where possible as it was considered an important part of the collection’s story.

In the absence of a conventional ‘story’, i.e. one that involves someone actually wearing the garments and leaving traces and imprints of wear (this could be a scent, creases or marks), such a decision makes sense. Fashion historians and costume conservators often talk of ‘sacred dirt’ – a lipstick trace here, a spot of blood there. These are marks that are integral to the story of the garment and must be kept intact.

There are some quite touching and intriguing examples of ‘sacred’ dirt within the Hodson Shop Collection. My personal favourite is the 1930s vest that features two small cat paw prints. I love the idea of a cat crawling over the piles of unsold underwear before snuggling down to sleep on a pile of knickers!

So, yes, I find dirt very interesting! But do museum audiences share my interest or do dirt and decay present insurmountable barriers for museum visitors? How can dirt and decay be presented to museum visitors? And at what point does a dirty and decayed item become unexhibitable?

This brings me on to what I have decided to call the ‘Tinkerbell’ dress (pictured above). The name comes from the fact that it is A) green and B) falling into a state of fairy-like shredded decay. It is an item that inhabits a state of limbo, being at once inside a museum but not part of the museum’s collection.

It is a beautiful pale green silk-chiffon dress from the 1920s that was found amongst the Hodson Shop stock. It has long lace-trimmed sleeves, a high lace collar and pretty scalloped pockets made from tiers of lace. I’m was initially quite surprised that the dress was from The Hodson Shop, mainly because it is silk, very bright and involves intricate detailing – such as the clusters of tiny silk wrapped balls that sit on the lace pockets. Most of the early Hodson Shop dresses are cotton or man-made fibres, fairly drab and simple. Sheila Shreeve believes that the dress may have been bought in especially for a friend or family member, thus explaining these differences.

The dress was discovered in such poor condition that it was decided not to accession it into the Hodson Shop Collection. The silk is shattered and shredding – so much so that I was terrified to move the dress to take a picture (hence the far from ideal images above – I’ll attempt to get a better one when I am next at the museum). Whilst this decay is sad, the dress is beautiful.

During her inaugural lecture at London College of Fashion, Amy de la Haye talked about exhibiting fragmentary and shattered garments, in relation to the Fashion and Fancy Dress exhibition of the Messel Family dress collection at Brighton Museum in 2005. According to de la Haye, fabric’s natural ability to ‘disintegrate with the progress of time’ reflects our own human fragility. She gave a wonderful quote from Anne Messel: ‘Their frailty is their magic, don’t you think?’

It was this thinking that lead to the inclusion of a shattered and fragmentary dress in the exhibition. It was laid flat – with its damage and decay exposed to visitors. It was ‘the unexhibitable exhibited’.

Interestingly, an image of a shattered corset worn by Maud Messel was used as the invite for de la Haye’s lecture (see below), suggesting that decayed garments can often make a lasting impression upon on those who come into contact with them.

Unlike the shattered Messel dress, the Tinkerbell dress has not been worn and it is not attached to an illustrious family of aristocratic fashion collectors. Maybe it is wear and attachment to a personality that make signs of decay palatable to museum visitors – are they what enable the unexhibitable to be exhibited?

Whilst the Tinkerbell dress is unlikely to ever be exhibited or accessioned, it has provided me with a lot to think about. I feel very lucky to have experienced this dress in all of its magic frailty.